By Jacki Swearingen and Vivian Lewis

Edited by Jim Harbison, Ryan O’Connell and Marilyn Go

With each election in recent years Florida has turned redder. In 2018 its voters elected one of the nation’s most conservative governors. However, this November’s outcome is a little less certain because of a recent decision by the Florida Supreme Court that allows a measure to ensure reproductive rights to be on the ballot this fall.

While President Joe Biden is still unlikely to garner Florida’s 30 electoral votes, a surge in voters determined to overturn one of the nation’s strictest abortion bans could benefit Democratic candidates further down the ballot. Although voter registrations for Democrats now trail those of Republicans by four percent, Democrats hope that they can convince the growing number of independents to vote for their candidates this November. Nonetheless, Democrats still face the possibility of reduced turnout because of strict voting laws Gov. Ron DeSantis and the Florida legislature put in place over the last three years.

Demographic Changes

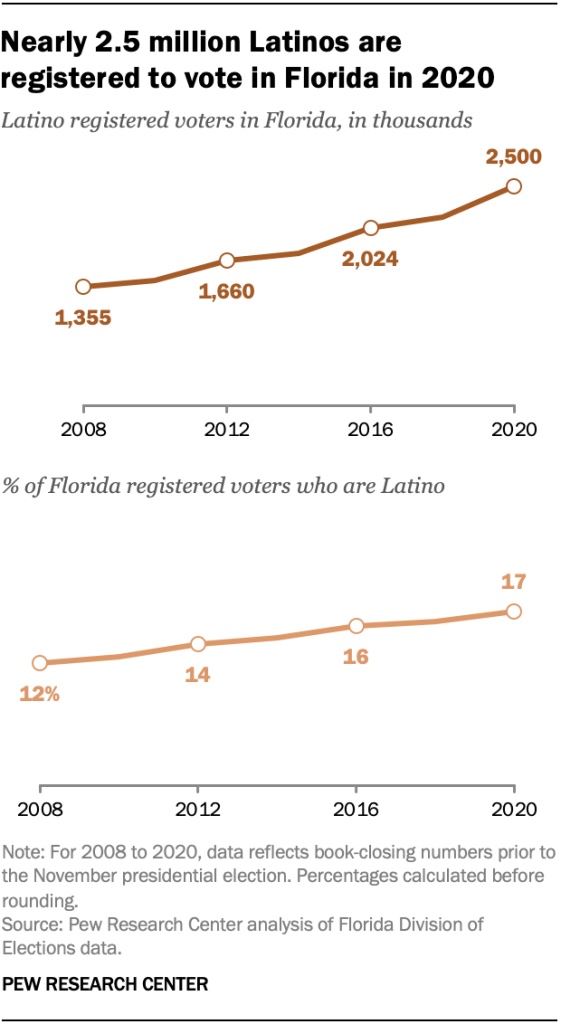

Just as in Georgia and Arizona, demographic changes in Florida have been accompanied by increased calls from Republicans to stamp out voter fraud. The 2020 U.S Census showed that among Florida’s population of 22 million residents, non-Hispanic white residents decreased to 51 percent from 58 percent in 2010. Hispanics, the fastest growing sector, grew to 27 percent from 22 percent ten years earlier. Floridians who are non-Hispanic African Americans decreased to 14.5 percent from 15.2 percent, and Asian-Americans increased to 3 percent from 2.4 percent.

Voter registration trends show that Florida is not easily pigeonholed into a red or blue niche, despite the outcomes of recent elections. More than one-third of the state’s registered voters are now non-white. The largest segment of Latinos remains Cuban-Americans who have overwhelmingly voted Republican since the first émigrés arrived in Miami in the 1960s. But Puerto Ricans, the second largest group, are more likely to vote Democratic. Indeed, the majority of Florida’s Hispanics are now registered as Democrats or independents, according to the James Madison Institute.

More people aged 60 to 69 moved to Florida than any other age cohort over the last decade. However, those aged 18 to 53 now outnumber Boomers in Florida. More and more of these younger voters are registering as “No Party Affiliation,” which helps to make independents the fastest growing group of Florida voters. Unaffiliated voters constitute 27 percent of registered voters while Republicans make up 37 percent and Democrats 33 percent.

Florida had some of the nation’s closest election outcomes in 2018 – a governor’s race DeSantis won by only 0.4 percent and a Senate race fellow Republican Rick Scott won by a mere 0.12 percent. However, the Covid pandemic contributed to a surge in Republican voters when DeSantis’s stand against lockdowns and other restrictions drew supporters from across the country. As DeSantis moved Florida further to the right on issues ranging from abortion to higher education, he also helped to bring into the GOP some long-time residents, particularly in North Florida who had regularly voted Democratic

Voter Suppression

Anxiety about the fragility of Republican victories as well as hopes of securing his party’s presidential nomination may have led Gov. Ron DeSantis to introduce strict voting control measures in 2021, which the Republican-led legislature speedily enacted. Law SB 90 limits where drop boxes for ballots can be placed, and it requires that the boxes be staffed during hours of operation. The law also restricts who can drop off a ballot for someone else, limiting this role to family members and caregivers, a change that voting rights advocates say places burdens on the disabled and seniors. Voters are also required to provide photo ID, a demand that the late Rep. John Lewis once likened to “a new poll tax.”

DeSantis and others claimed that they were tightening voting laws to combat voting fraud. However, a 2023 Brookings Institution report concluded:

“In Florida, there were nine cases of election fraud between the 2020 and 2022 elections but many of those involved individuals who were confused over whether or not they had the right to vote.”

Despite lack of evidence of any significant voter fraud, DeSantis signed a law in April 2022 that established a new state security office to investigate claims of voter fraud and arrest those charged with it. The new “election police force” ended up arresting only about 20 people in 2022 for casting illegal ballots. Nearly all those accused were shown to lack criminal intent and their cases were eventually dropped.

These arrests stirred fears in some voters that they might be apprehended for voting in error. Many of these citizens were former felons whose right to vote was restored in 2018 by an amendment to the Florida Constitution that 65 percent of voters approved. Nonetheless, DeSantis and the legislature have undermined the amendment by enacting a law that prohibits former felons from regaining their right to vote unless they have paid off fines imposed by the courts as part of their conviction.

The Brennan Center and other voting rights groups challenged this law as unconstitutional, but the US Eleventh Circuit Court has allowed it to remain in place. In the 2024 election cycle an estimated 935,000 Floridians who have completed their sentences but not paid their fines will be unable to vote, according to the Sentencing Project.

Redistricting

DeSantis and the Florida legislature have also drawn fire for enacting a 2022 redistricting map for Congressional districts that voting and civil rights advocacy groups say is racially discriminatory. The reconfigured maps, they argued after the 2022 election, were designed to ensure the defeat of three-term Rep. Al Lawson, a Black Democrat, as well as to dilute the power of Black voters in other districts by moving many of them into overwhelmingly white and conservative districts. Their challenge wended its way through the courts until February of this year, when the Florida Supreme Court issued a one-sentence order saying that it would not speed up consideration of the case in time for the 2024 election. The contested maps will remain in place.

Voter Registration Obstacles

Law SB 7050, which allowed DeSantis to run for president without having to resign as governor, also builds on the changes to Florida election law enacted in 2021. The latest law imposes stringent new requirements on third-party voter registration organizations and quintuples the maximum fines these groups can incur. The measure bars non-citizens from handling or collecting voter applications as part of an effort by a third-party group to register voters. The new restraints have drawn the ire of Hispanic and Black voter advocacy groups, which argued that non-white voters often rely on their organizations to help them register.

Increasing the obstacles to mail-in voting, the new law mandates that voters can pick up a mail-in ballot only if they are unable to vote in person at an early voting location or at their assigned polling place on Election Day. Only family members can now request a mail-in ballot on behalf of a voter.

Finally, critics of SB 7050 maintain that the new law will cause more registered voters to be purged from the rolls. Election officials can decide to remove a voter based on any “official” source rather than relying solely on ID sources specified in existing law. The new law also accelerates the process of removing voters from the rolls.

Outraged by these new rules, the NAACP, the League of Women Voters, the ACLU and other voting advocacy groups filed two separate lawsuits. The League of Women Voters in Florida said in a statement released the day DeSantis signed the bill:

“The law, Senate Bill 7050, directly targets and drastically restricts the ability of nonpartisan civic engagement organizations, like the League of Women Voters of Florida, to engage with voters, violating their right to freedom of speech and association.”

On March 1 Obama-appointed Chief US District Judge Mark E. Walker struck down the provision in the law that prevents non-citizens from collecting or handling voter registration applications on behalf of third-party organizations. Judge Walker ruled that the prohibition violates the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment. However, Judge Walker’s decision only prohibits Florida’ secretary of state from enforcing that part of the law; he did not prevent the state’s attorney general from applying it. A second trial is now underway in Tallahassee before Judge Walker in which voting rights organizations seek to extend that prohibition on enforcement to the state attorney general as well.

Voter registration advocates who argue that SB 7050’s restrictions and penalties have already depressed 2024 voter registration drives continue to face challenges in overturning the measure. After Judge Walker’s ruling, Florida officials appealed to the 11th Circuit Court of Appeals in Tallahassee. That case is still pending.

Abortion Rights

In recent weeks the Supreme Court judges, all appointed by Republican governors, have played a pivotal role in the fight over abortion rights. The Florida State legislature passed several bills in 2023 that affect reproductive freedom, including the Heartbeat Protection Act that restricts access to abortion after six weeks’ gestation. The controversial legislation prompted a grassroots effort to mount a ballot initiative to amend the constitution, which garnered almost a million signatures. Proposed Amendment 4 to the Florida State constitution would preserve the right to abortion until 24 weeks. The Florida Supreme Court allowed the six-week ban to go into effect and approved the final language of the ballot initiative on April 1.

For the amendment to become part of the constitution, 60% of voters must approve it. Backers of the proposed amendment include Floridians Protecting Freedom, Planned Parenthood, League of Women Voters Florida and the SEIU (Service Employees International Union). Florida Voice for the Unborn and Florida Council of Catholic Bishops are among opponents to the proposal. Of note, this amendment may not settle the issue as Florida Supreme Court justices have signaled a willingness to separately consider the issue of fetal rights.Down-ballot primaries in August will also provide an opportunity for voters to learn the national and state candidates’ positions on a host of issues affecting reproductive freedom, including access to gender-affirming care, bathrooms and in vitro fertilization.

Important Down Ballot Races

While the presidential election will be at the forefront this November, Florida has a number of down ballot races that could also affect the nation as well. Democrats will select a candidate in the August 20th Florida primary to challenge Republican Rick Scott, the former governor who was elected to the Senate in 2018. Scott is regarded as one of the most vulnerable Senate incumbents in this election cycle in part because of his stance on Social Security, Medicare and abortion. Twenty-eight House seats will also be up for grabs, including a new one awarded to Florida after the 2020 Census. Finally, Floridians will have the chance to vote on Amendment 3 to the state constitution, which would legalize the use of marijuana for adults 21 and older.

Get Out the Vote

What role can you play? Take part in this election by registering voters, phone banking and canvassing. Sign up as a poll worker. Help cure mail-in ballots to prevent a ballot from being discarded because of an error that could easily be fixed.

Florida lawyers can lend their skills to organizations like Florida Election Protection Coalition that aids voters who find their right to vote challenged at the polls. Lawyers can also help assess accessibility at polls before voting occurs.

These organizations are also playing an active part in working for free and fair elections in Florida:

League of Women Voters of Florida “registers, empowers, and educates voters” as well as advocates for fair voting laws.

Common Cause Florida advocates for fair voting laws and helps voters with individual questions. Both Common Cause and America Votes helped cure Florida mail-in ballots in the 2020 election.

Black Voters Matter works in Florida and 24 other states to register voters and get them to the polls. Their “We Fight Back” bus tour is headed to Florida May 16 to May 20.

Movement Voter Fund helps support Florida voter organizations that focus on Latinos.

Equality Florida focuses on the LGBTQ community to register, educate, and transport voters to the polls.

The Andrew Goodman Foundation seeks to increase voter registration among college students and inspire them to get out the vote.

The Florida Justice Center helps former felons regain their right to vote.